Wild Summer

Headlands Center for the Arts' Summer 2022 Open Studio

During a six-week residency in the Marin Headlands, while working on a new fiction project, I carried a camera and covered more than 350 miles of trail. I ran, walked, and meandered while noting the nonhuman life I encountered on my way: from song sparrows to peregrine falcons, Italian thistle plants to coast lupine bushes, and gopher snakes to river otters, I was an awestruck visitor in a park that was home to an exceptional number of species. The Headlands region is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, one of the most biodiverse places on the planet and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

I was also looking for escape and answers to big questions, but that part of the journey is something I can express better in fiction. What I wanted to show the world through the tiny lens of my studio was an expression of curiosity and unending discovery.

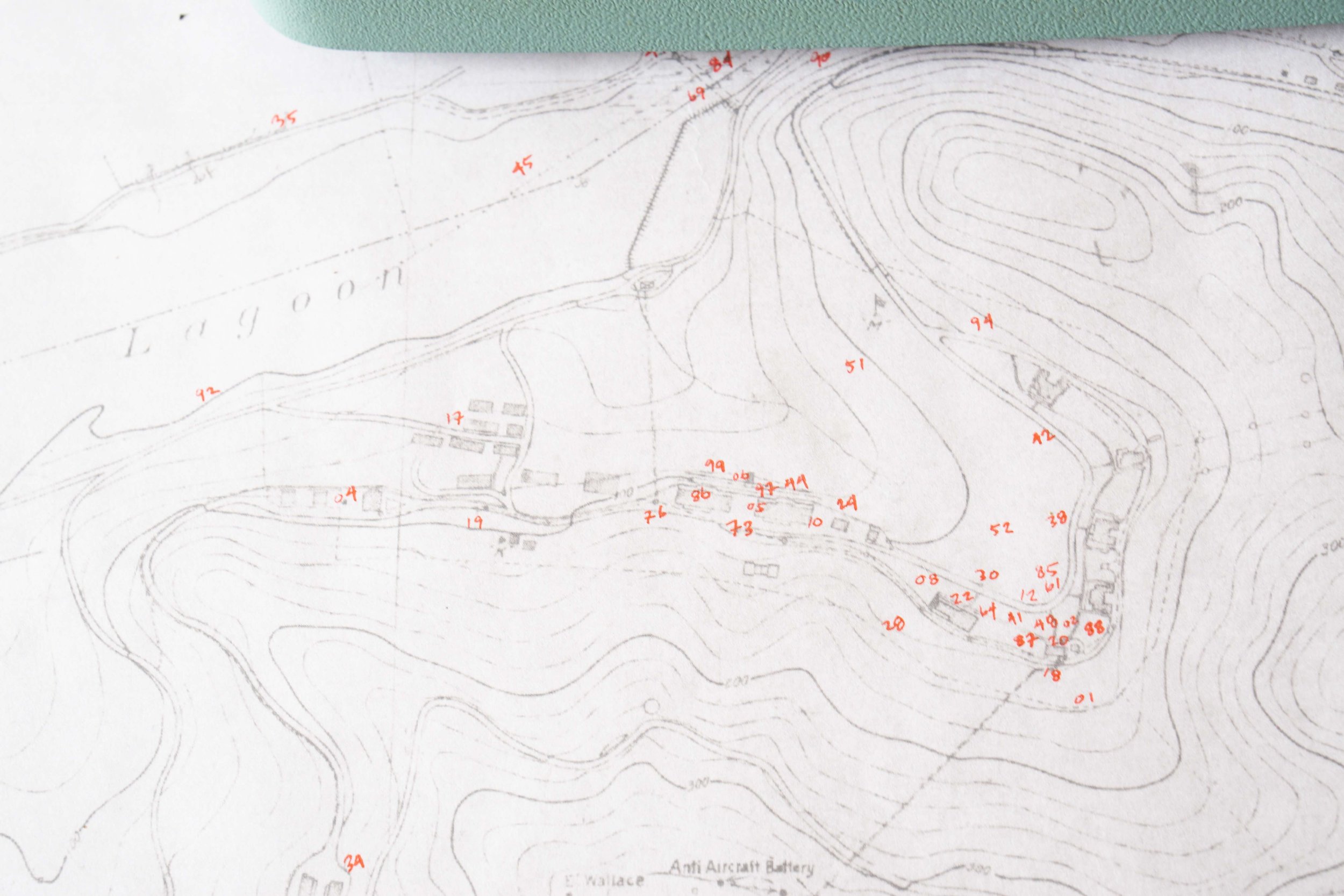

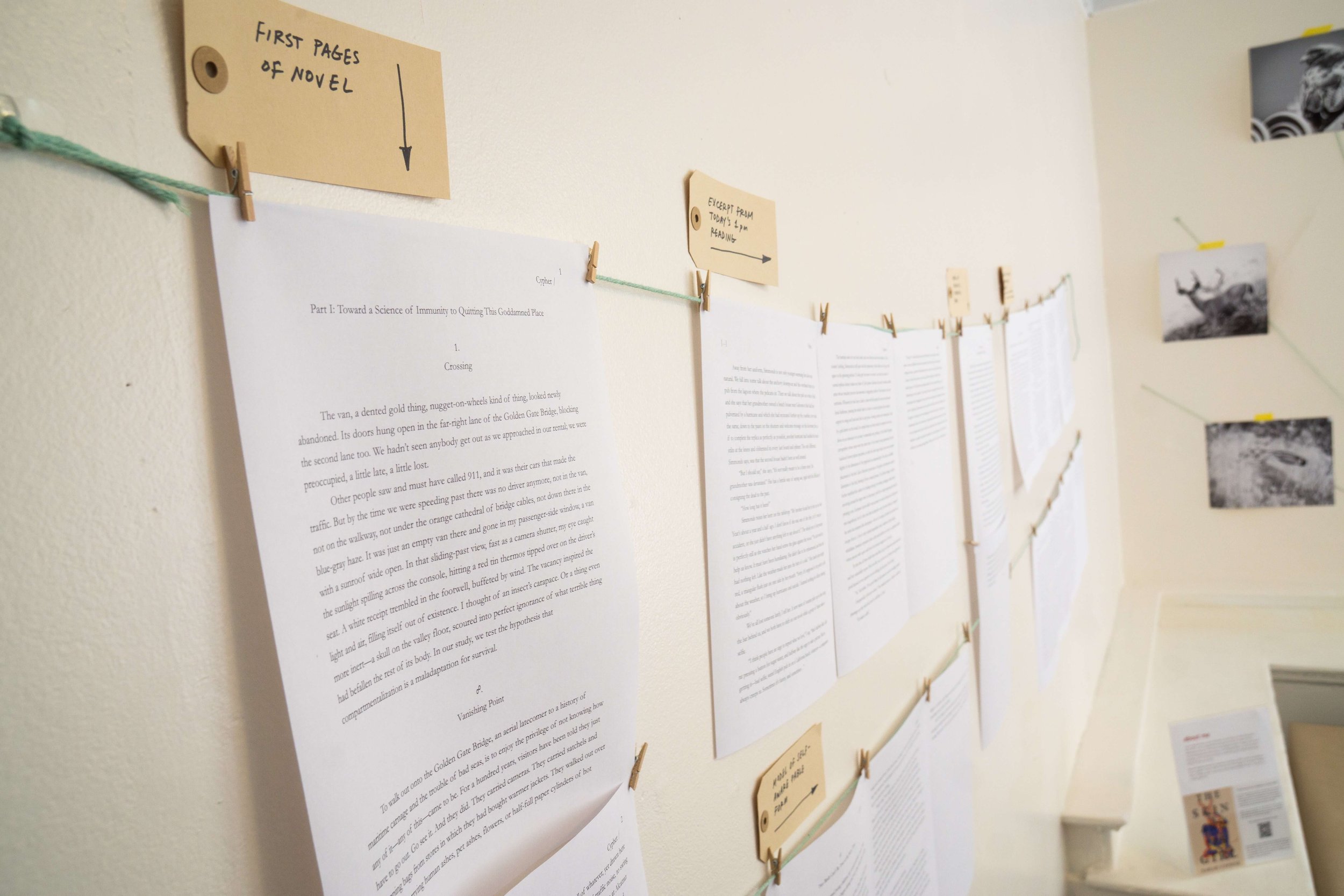

I wanted an interesting way of representing what I encountered, when, and where. First, I obtained a topographical map of the area from the Presidio Archives and Records Center (on its own, a fascinating biopsy of the area through time). Second, I created a series of tags: each of the ninety-nine species I chose to feature has a number that corresponds to the map. Each tag lists both a scientific and common name, a way of representing how we humans try to pin down and “settle” our knowledge of our environment through words and taxonomy. The exact temporal center of my residency aligned with the summer solstice, and the position of the species’ tags that arc along the wall in the photo above correspond to the point in time I encountered them: the deer, for instance, were there from the beginning, but it took a while to encounter the river otters.

The result is part field journal, part broken clock. The appearance of order is as illusory as any other symbolic form: while this display represents ninety-nine species, I encountered many of them more than once, and over 160 separate species in total. I’m sure there are many more I didn’t observe. The record, like a novel, is subjective. About a third of the tags have a small journal entry on the back, corresponding to a daily journal I kept, detailing my subjective impressions of an encounter. For instance, here is the one for Lepus californicus, the black-tailed jackrabbit:

Seen high on the hills, often in the morning. The 6/28 run was my “jackrabbit run”: saw five in total, which seemed like a lot. The first jackrabbit was large enough to make me think it was a small coyote (and perhaps was the same one I saw weeks before, since I saw it in the exact place). Black-tipped ears stood out in the heavy fog. I ran past without hardly looking because the rabbits seem very sensitive to attention, more so than every other animal I’ve encountered except the deer; so this time, the rabbit only hopped to the higher side of the trail and waited for me to pass, wary but not panicked. The back of the rabbit’s head was so white-pink that I thought it might be an injury: bare skin with no fur. But no—all the jackrabbits I saw this morning had the same white back-of-head and feet. As I ran on, I saw three more adults. The fifth and final jackrabbit was very young, no bigger than the adult brush rabbits, and I worry about its longevity: from twenty feet in front of me, it began to run, but not away: zigzagged directly toward me and passed within a foot of my right shoe before dashing onward and finally into the grass. I could have touched its ears.

I’m a writer, not an artist. And I’m a body in motion with a camera, not a photographer or naturalist. But, as someone constantly engaged in semiosis and the process of representation, I often think about what written language can and can’t tell us about our world—including how to exist in it with equipoise. Human communication fails us, and we fail our ecosystem. My work seeks ways of using language and unconventional storytelling to shift how we engage with our endangered environment. The exhibition below was an exercise in deep observation, one that negotiates self-awareness with a wider ecological awareness, as well as the tension between individuals and their species.

I am especially grateful to Headlands Center for the Arts for the support, time, and space to pursue an interdisciplinary approach to my craft in my new novel’s setting. It accelerated the process of finding my footing in a new project, and it enabled a rich research process that would have been possible nowhere else. I am also grateful to Amanda Williford of the Presidio Archives and Records Center, wildlife ecologist Dr. Bill Merkle, and Ranger Fatima Colindres, all of the National Park Service, for their assistance in interpreting the Golden Gate National Recreation Area’s history and ecology for my ongoing project.